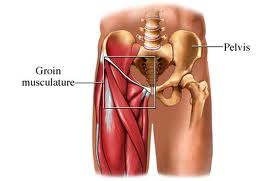

Clinical Features And Treatment of Groin Pain: The Iliopsoas muscles may be the sole cause of the athletes longstanding groin pain, but this component is frequently present in conjunction with adductor abnormalities. The Iliopsoas component needs to be recognized and subsequently treated.

The Iliopsoas muscles may be the sole cause of the athletes longstanding groin pain, but this component is frequently present in conjunction with adductor abnormalities. The Iliopsoas component needs to be recognized and subsequently treated.

The Iliopsoas muscle is the strongest flexor of the hip joint. It arises from the five lumbar vertebrae and the ilium and inserts into the lesser trochanter of the femur. It is occasionally injured acutely but frequently becomes tight with neural restriction. Whether or not Iliopsoas tendinopathy and bursitis contribute substantially to exercise-related groin pain remains unclear. Most case reports associate these conditions with hip surgery and with rheumatological conditions (e.g. polymyalgia rheumatic). The thin-walled Iliopsoas bursa commonly communicates with the hip joint. Experienced clinicians feel that muscular and neuromyo fascial elements are likely to contribute far more commonly than do Iliopsoas bursitis and tendinopathy.

Clinical Features

Iliopsoas problems may occur as an overuse injury resulting from excessive hip flexion, such as kicking. They present as a poorly localized ache that patients usually describe as being a deep ache in one side of the groin. There are two key clinical signs that point to the Iliopsoas as the source of groin pain.

- The first, tenderness of the muscle in the lower abdomen, relies on palpation of the Iliopsoas muscle, which is difficult in its proximal portion, deep within the pelvis.

- Nevertheless, the skilled examiner may detect tenderness more distally, particularly in thin athletes, by palpating carefully just below the inguinal ligament, lateral to the femoral artery and medial to the Sartorius muscles.

- Passive hip flexion facilitates this palpation.

- The second key clinical sign that helps distinguish the Iliopsoas from other sources of groin pain is pain and tightness on Iliopsoas stretch that is exacerbated on resisted hip flexion in the stretch position.

- Frequently, the further addition of passive cervical flexion and knee flexion will aggravate the pain, indicating a degree of neural restriction through the muscle.

- It is important to examine the lumbar spine as there is frequently an association between Iliopsoas tightness and hypomobility of the upper lumbar spine from which the muscle originates.

Treatment

Treatment of Iliopsoas-related groin pain is similar to that of adductor-related groin pain but with an increased emphasis on soft tissue treatment of the Iliopsoas and Iliopsoas stretching with the addition of a neural component. Often, mobilization of the lumbar intervertebral joints at the origin of the Iliopsoas muscles will markedly decrease the patient’s pain.

The article presents clinical examination of athletes with groin pain. Clinical examination techniques that are used to diagnose and evaluate the degree of groin pain in athletes have not been well evaluated.Active Physical Therapy provides our services include and are not limited to physical therapy, occupational therapy, hand therapy, senior wellness, neurological rehabilitation, orthopedic rehabilitation, industrial rehabilitation and specialties including auto accident injuries / Trauma Cases, Work-related Injuries, Sports Injuries, Tennis Elbow,etc. For More Detailed Information Call Now at: 301-498-1604